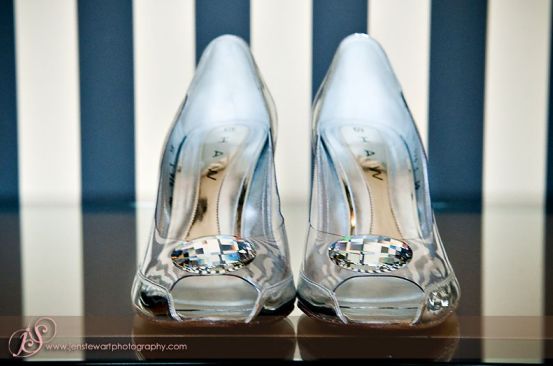

(Photo credits: via Vintage Glam Weddings, photo by Jen Stewart Photography)

(Photo credits: via Vintage Glam Weddings, photo by Jen Stewart Photography)What would you be willing to do if all that stood between you and your idea of a perfect future was a few shoe sizes? Cinderella’s step sisters were willing to cut of toes and bits of their heels for the chance to be royalty, and they were encouraged by their mother! She told them that they wouldn’t really need their feet once they became queen. This part of “the best known fairy story in the world”, which can be found the Brothers Grimm telling, was not included in the Disney adaptation of Cinderella.

The versions of Cinderella that have been adapted to stage plays and musicals, films, and various retellings, including Ella Enchanted by Gail Carson Levine, were based on Charles Perrault’s or Pierre Perrault’s variation of the tale published in Paris in the late 17th century. In the early 19th century the Grimm Brothers, “determined to preserve Germanic folktales”, recorder the German edition of a fairy-tale involving a heroin who is mistreated by her stepfamily and eventually marries the prince. Also in the late 1800s, Andrew Lang came across a version of this story in Scotland referred to as “Rashin Coatie”. Sure the heroine in this rendition has 3 evil step sisters rather than two, has a different nick-name, and is dressed in a coat made of rushes, but she is still too dirty and poorly dressed to attend the ball. She is granted appropriate clothing by the dead body of a red calf given to Rashin Coatie by her mother before she passed away (both the red calf and Cinder-Rashin-Lady’s mother were alive when the calf was given as a gift), and wins the heart of the prince.

China even has its own versions of Cinderella, some that can be traced by to the 9th century, each with animals that help the main character to overcome the plight brought on them by their step families. Interestingly, most of the versions of Cinderella don’t involve a fairy godmother at all, but rather heroin is helped by her mother’s spirit, or objects/animals that were sent to guard her, or given her by her mother. The Perrault version is where the actual fairy godmother enters the story. Each telling is unique, and there are actually over 300 versions, but they all involve a kind hearted girl who is treated maliciously by her step-mother and step-sisters and a shoe that helps her land her man.

Citations:

Parsons, L. (2004). Ella Evolving: Cinderella Stories and the Construction of Gender-Appropriate Behavior. Children's Literature in Education, 35(2), 135-154. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database.

Ashliman, D. (2010). Grimm brothers’ home page. Retrieved from http://www.pitt.edu.

(1999) Grimms’ fairy tales. Retrieved from http://www.nationalgeographic.com/.

Opie P., Opie I. (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales: Cinderella, 117-127. New York, Oxford; Oxford University Press.

Owens, L. (1981). The Complete Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales. New York, Toronto, London, Sydney, Auckland; Crown Publishers, Inc., Random House.

(1975). THE CHINESE CINDERELLA. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 4(2), 10. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database.

Huang, B. (2001, July 6). The origin and evolution of fairy tales. Retrieved from http://www.bobhuang.com/essays/essay22.htm